The Publishing Black Box: What happens after you click Submit?

Every one of us researchers has, as some point in their career, to go through the process of submitting a paper and all those who have submitted – and even those who as yet have not – know some detail of what happens behind the curtains. But who really knows the whole process? Here we try to get into the details of what happens from submission to the final response.

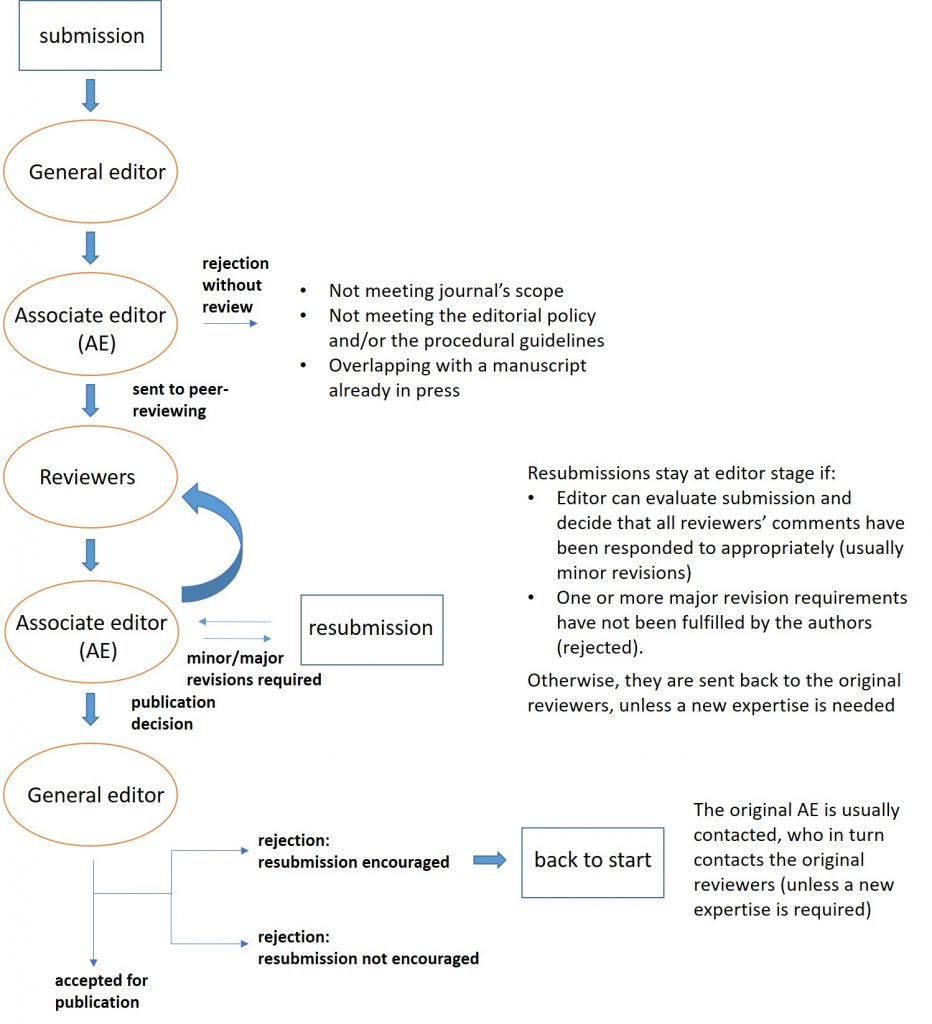

The submission is received by an editor who also handles general administration tasks and collects all submitted manuscripts: an Editor-in-Chief or Executive Editor, who manages all editors, or a Senior Editor, with intermediate responsibilities, or a Managing Editor or just… an Editor. I will call this role “general editor” here, for simplicity. She/he assigns each submission to an Associate Editor (AE) with expertise in the relevant field. The AE is usually an active researcher (although some journals also enroll senior scientists as their AEs), who can better understand the content of the submission and its relevance to the field and the scope of the journal.

The first stage of a submitted article’s publishing process is assessing its fit to the journal’s scope. This is done by the general editor, based, first of all, on the cover letter attached (if any – don’t neglect adding one!) and sometimes after consulting with the AE, given her/his better overview of the specific topic. The general editor also considers whether the submission fits other journal requirements (does it meet the editorial policy? did the submission respect the procedural guidelines outlined on the website?). Finally, a manuscript may be rejected at this stage if there is a large overlap in content with other submissions that have already reached the press stage. The authors might be invited to resubmit the work, despite rejection, if the reasons for refusal can be addressed to produce a manuscript suitable for the journal. However, invitation to resubmit should not be interpreted as a guarantee that the new version will be accepted.

If a manuscript’s content is considered of interest and all other preliminary criteria are met, the manuscript is passed on to the AE, who finds researchers with the right expertise to act as reviewers. How editors track down relevant potential reviewers is a topic that, alone, would deserve a full blog post – luckily there is already an excellent one on the blog by Stephen Heard, so have a look there if you are interested.

Reviewers must be 1. technically competent to evaluate the work (perhaps having recently written a paper on a similar topic), 2. independent from the author and the author’s institution (often a reviewer working in a different country from the main author will be contacted) and, importantly for the journal’s workflow, 3. available to assess the submission within the time required by the journal. Each submission will be most commonly evaluated by two reviewers, sometimes more, if an extra area of competency needs to be covered, rarely one.

The two most common types of peer-reviewing are single-blinded and double-blinded review. In these review setups, the reviewer’s name remains unknown, and in the double-blinded setup the authors are also anonymous to the reviewer throughout the review process. These systems are meant to ensure the impartiality of the process, by removing any direct link between the two parties. Further concerns about bias towards the author’s institution, nationality, gender or other personal details have lately been addressed through an increasing use of double-blinded peer reviewing – that was, until recently, under-utilised in the sciences. A third setup, open peer-reviewing, where the reviewer’s name and sometimes review are made public, is meant to encourage good quality reviewing by associating the output to the reviewer’s name. This latest setup has been recently officially introduced by some journals.

A manuscript being directly accepted for publication is an exceptional event. Usually, one of the editors will return to the corresponding author with a list of minor or major revisions required by reviewers. If the AE feels the need for senior expertise to help her evaluate the reviewers’ opinions, she will contact the editor a step up in the responsibility tier (a Senior Editor, or the Editor-in-Chief).

If revisions are minor and the authors address them very clearly in the resubmitted manuscript (and in the attached reply to the reviewers), the article might stay with the AE, who will evaluate the new version and then submit her recommendation of acceptance to the general editor. Otherwise, the document is sent back to the original set of reviewers (usually), who will judge whether their requests have been met appropriately and submit their revised opinion to the AE. Sometimes, more than one round of resubmission and review is needed to assess and develop a manuscript.

Reviewers might recommend acceptance or rejection of a paper, based on their understanding of its relevance to the field and on their critical evaluation of the technical quality and scientific validity of the study. However, the final decision is made by the editor, who takes notice of their view before deciding whether the new version of the article belongs to the journal. While an accepted manuscript proceeds to publication, a rejection might once again come with an invitation to resubmit, once the pitfalls that led to refusal have been addressed. Rejection without invitation to resubmit might be appealed with a letter to the editor explaining how the reviewers or editor herself failed to see critical aspects of the work that would address the reasons for rejection. However, appeals of this type must be strongly motivated to be accepted!

Processing a manuscript is a balance between technical and scientific evaluation of the article and qualitative evaluation of the subject topic from the journal’s point of view. We wish you good luck with your submissions!

Thanks to

Dr Catherine Sheard was a precious source of information for this article, in her role as an Associate Editor and as a well-travelled researcher in the world of scientific publishing. Catherine is a postdoctoral scientist working on bird and language phylogenies. She runs multiple amazing Twitter accounts filled with facts about birds and research. Check out her personal one, @sheardcat

References

Voigt and Hoogenboom (2012). Publishing your work in a journal: Understanding the peer review process. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 7(5):452-460.

Nature – Editorial criteria and processes. Available at: https://www.nature.com/nature/for-authors/editorial-criteria-and-processes (Last accessed: 20/01/2019)

De Coursey (2006). Perspective: The pros and cons of open peer review. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature04991 (Last accessed: 27/01/2019)