The PanAf project: studying chimpanzee culture across Africa

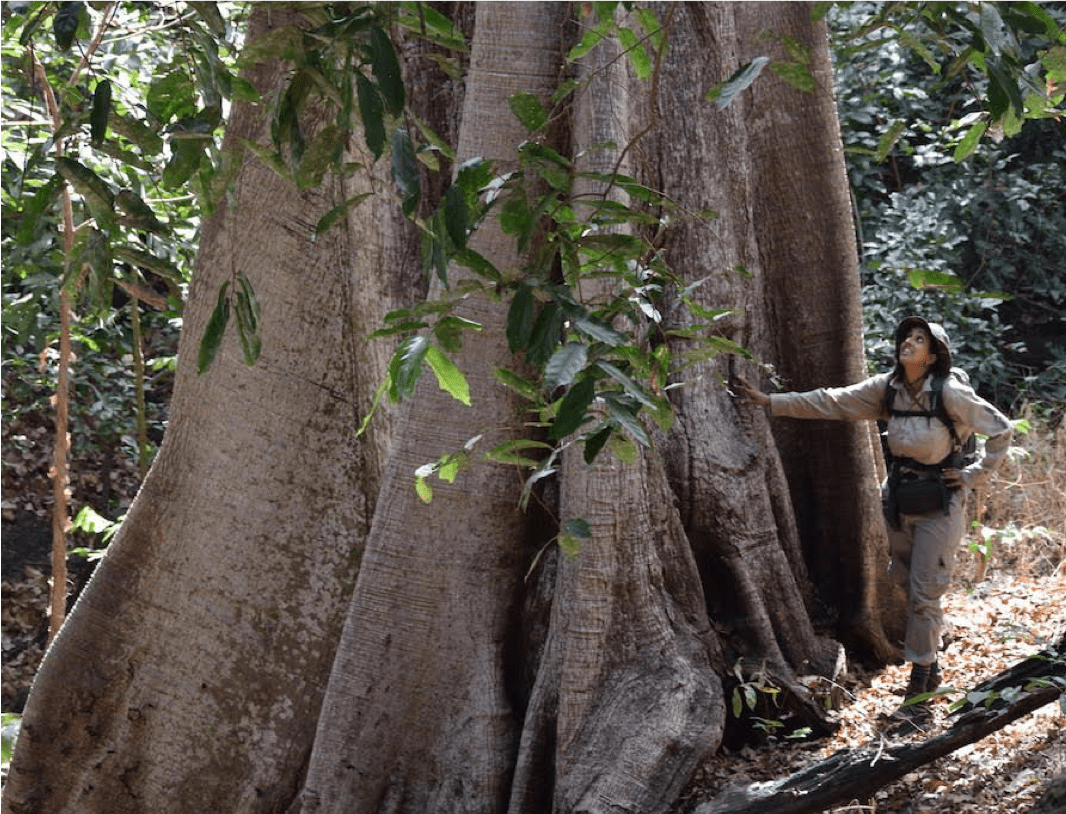

Ammie Kalan is a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, investigating chimpanzee communicative behaviour within a cultural framework to contribute to our understanding of the behavioural flexibility of these animals. Her work is conducted as part of the Pan African Programme: The Cultured Chimpanzee. Her doctoral thesis investigated wild chimpanzee acoustic communication, where she also helped to develop a novel method for using vocalizations and auditory signals as a monitoring tool for primates living in a tropical rainforest. She continues to be interested in bridging the gap between behavioural research and applied conservation and hopes to continue working on non-invasive monitoring methods.

Ammie spoke to Cultured Scene about her work on the PanAf project and her recent findings.

Cultured Scene: Could you please tell us a bit about your background and your research? What is your main line of work?

Ammie Kalan: I am trained as a biologist, having done my undergraduate degree in Zoology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, where I was born and raised. From the age of 10 I dreamed of being a primatologist, so after my undergrad I went to the UK to pursue an MSc in Primate Conservation at Oxford Brookes University. Here, I was able to begin my primatology networking and was lucky enough to go to the Lac Télé Community Reserve in the northern Republic of Congo to study wild gorillas with the help of the Wildlife Conservation Society. In Lac Télé, I encountered the most beautiful rainforest I have ever been in, with lush biodiversity including wild gorillas and chimpanzees. That experience solidified my desire to pursue a PhD in field primatology. I was again quite lucky, I think, and moved to Leipzig, Germany to begin a PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, where I spent almost two years in the Taï forest, Côte d’Ivoire. My doctoral research focused on chimpanzee vocal communication, particularly the use and variation in food grunts. At the same time I developed novel methods for passive acoustic monitoring of forest primates. After my PhD, my supervisors asked me to join the PanAf project as a post-doc and I was very excited to work on this project where I could expand on my interests in communication and biomonitoring by investigating chimpanzee tool-use, culture and camera-traps.

CS: What is the PanAf project and how did it start?

AK: The Pan African Project: the Cultured Chimpanzee, or simply ‘PanAf’, was initiated in 2010 by Hjalmar Kühl and Christophe Boesch and is also co-directed by Mimi Arandjelovic (http://panafrican.eva.mpg.de/index.php). The aim was to substantially increase the sample size of chimpanzee communities to better understand drivers of behavioural and cultural diversity across their natural range. To achieve this, the PanAf conducted vigorous, standardized, non-invasive data collection at locations where chimpanzees were known to exist but virtually nothing was known about them. More than 40 temporary research sites were initiated by the PanAf since 2010 with the majority resulting in data collected continuously for 1-2 years at these sites.

CS: What have we learned so far thanks to the PanAf project that we couldn’t have discovered otherwise?

AK: It was predicted that there might still be chimpanzee behaviours undiscovered because only a small fraction of chimpanzee populations had been studied until now, and in fact we were right! I think we were all amazed by finding new behaviours during the PanAf, like chimpanzee accumulative stone throwing and algae fishing. By comparing the presence of these behaviours across all other PanAf sites and known long-term research sites, it is clear that these behaviours are quite unique and may even be cultural.

CS: How has your experience so far been with collaborating with the broad network of scientists involved in the PanAf project?

AK: The success of the PanAf depends on the collaborative nature of so many researchers and conservationists, who help us in a multitude of ways, such as organizing logistics and permits, giving us access to their sites, helping with data collection or contributing data. This is also why we publish papers that have many co-authors, because the PanAf is only possible due to the contribution of so many. This also includes our dedicated, hard-working PanAf site managers. I personally find myself quite fortunate to be working with so many scientists that I respect and admire and to get this amazing insight into the diversity present in chimpanzee populations and their habitats across Africa. I have also been lucky enough to visit other field sites as part of the PanAf, such as Issa in Tanzania.

CS: What are the main challenges of such large projects? In your experience, what is the best way to overcome them?

AK: The amount of data you accumulate is the biggest problem. There is so much, so fast that it is hard to keep control over everything. Having a dedicated data manager and data cleaning team is really important. We also have a citizen science project, Chimp&See, which has been incredibly helpful and rewarding at the same time. On this platform we have thousands of citizen scientists helping us to identify which animal species are in our camera-trap videos, and even more, helping to identify individual chimpanzees. Chimp&See recently helped me with one of my latest publications, investigating novelty responses to camera-traps where we asked citizen scientists to help us find and tag camera reaction videos. The website (chimpandsee.org) is being revamped at the moment and will be back better than ever including a multilingual interface, so stay tuned!

In such a large project another important piece of advice I can offer is the importance of communication. It is often difficult and time-consuming to ensure all individuals who contributed to the success of a particular project have a voice in the final product, but it is key to maintaining trust in collaborations.

CS: You recently published a paper with data from the PanAf project in Science analyzing the relationship between human impact and chimpanzee culture. What was the main finding of that research project?

AK: We found that chimpanzee communities living in areas with a high human footprint (a global, freely available GIS layer) had reduced behavioural diversity. Since many of the behaviours we investigated were those that demonstrated cultural or population variation in previous studies, we inferred that anthropogenic impacts are contributing to the loss of wild chimpanzee cultures. This was a depressing but important finding, since it was the first time we could show that not only does human destruction lead to a decline in wildlife populations and genetic viability, but this destruction also manifests at the behavioural level.

CS: How can the PanAf project contribute to the conservation of great apes?

AK: In our Science paper we put forth the idea of ‘chimpanzee cultural heritage sites’ to draw attention to the fact that we value and preserve places and populations that contribute to humankind’s rich cultural history, so perhaps we should similarly value the cultural heritage of other species, like chimpanzees. We hope this idea will stir some discussion among scholars and conservationists and might eventually be considered as an additional aspect to be integrated into conservation action plans and the like.

CS: Which questions would you like to answer in the future with this project?

AK: I would like to use the PanAf data to investigate predator-prey interactions, something we know very little about but was likely a significant evolutionary force for primate societies. I am also following up on our Science paper by examining drivers of behavioural diversification rather than eradication. I was also able to start my own research project, with help from the National Geographic Explorers fund and support from the Chimbo Foundation, to investigate chimpanzee accumulative stone throwing in more depth. I have been analyzing data we collected in the field during 2017 and I hope to have some results published soon on this strange and interesting behaviour.