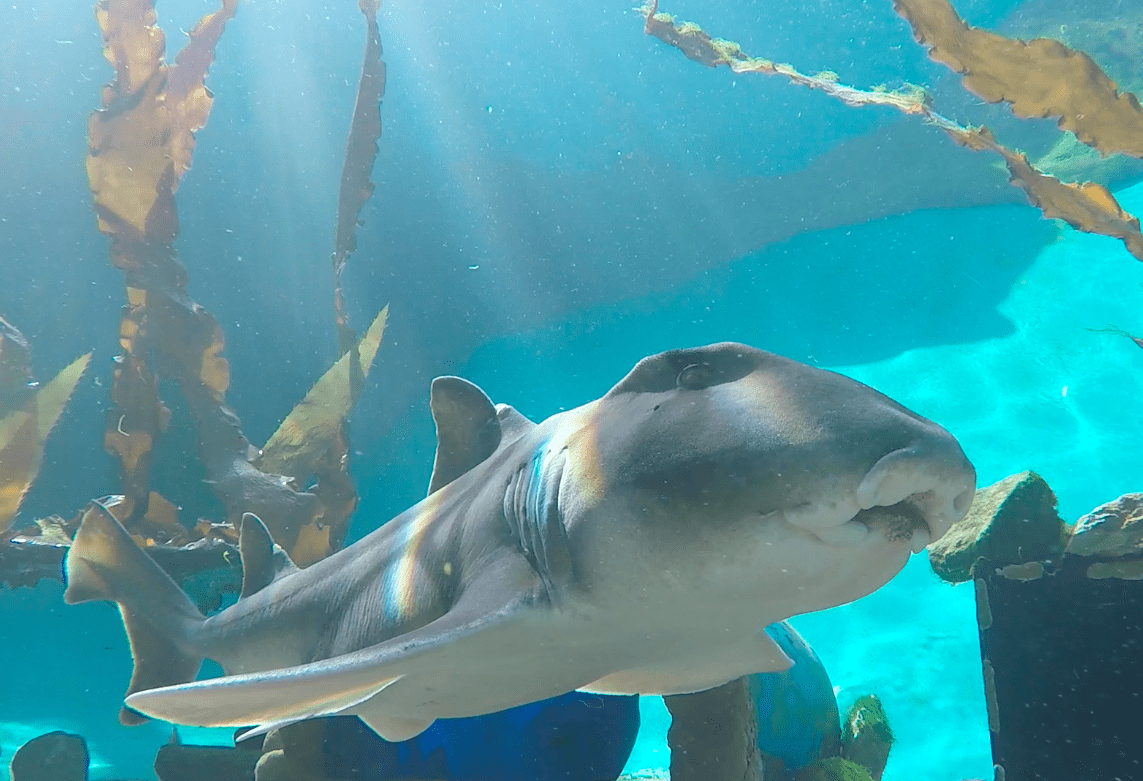

Of sharks and their ability to learn from others

Catarina Vila Pouca spoke to Cultured Scene about her findings on social learning in juvenile Port Jackson sharks that have been published in Animal Behaviour earlier this year.

The paper

Cultured Scene: What is the key finding of your study?

Catarina Vila Pouca: The main finding is that even a bottom-dwelling, solitary shark can learn faster by watching and interacting with other sharks. For many decades, the ability to learn from others was considered an advanced skill of ‘higher’ animal groups. Our study, together with many recent works on shark learning abilities, shows once again that sharks are intelligent and complex animals.

Another interesting finding was that sharks that were trained three times each day learnt just as fast as those that did six trials per day. In human psychology research, it is known that students learn and memorise things better if they space out their study sessions with rest and sleep intervals, compared to long, massed-practice schedules. Sharks might have similar learning and memory processes, since the shorter 3-day sessions allowed them to learn just as good as longer training schedules.

CS: Why is this topic important, and how do you feel it relates to social learning and cultural evolution more broadly?

CVP: Much of the technological developments over human history are the result of social learning. Culture and traditions ensure the passing of information from one generation to the next, and enable a cumulative gain in information and sophistication. However, this social transfer of information is not unique to humans, and in fact has a long evolutionary history. Some early examples of social learning and culture in animals were shown in populations of primates and birds. Researchers have since shown that social learning is also widespread in other animal groups, including bony fishes, where social traditions play important roles in the movement and migration of a range of species. But in elasmobranchs (sharks and rays), social cognition is severely understudied. Elasmobranchs are at the base of the vertebrate evolutionary tree, and so they offer the possibility for an inclusive view of how social learning and culture have evolved throughout the animal kingdom. By looking at a range of species from different ecological and social niches, we could examine which factors might have contributed to the evolution of social cognition in elasmobranchs, and if social cognition hypotheses developed in birds and mammals also hold true for this group.

The process

CS: How did you arrive at the idea for the study?

CVP: My field of research is fish behaviour and cognition, so I am naturally interested in what bony fish and sharks can learn from their environment, and how they come to learn them. My lab at the time (The Fish Lab, Macquarie University) was working with Port Jackson sharks, and social behaviour was one of the topics. Port Jackson sharks are a nocturnal, benthic species from Australia, and adults forms social groups during the breeding season. On the east coast of Australia, these sharks undertake a migration of hundreds of kilometres south, only to return the following year to their preferred location and group with the same individuals. A study showed that their breeding aggregation sites have been used for more than 50 years, and it was suggested that their migration routes are passed on through social learning. For this to be possible, we first had to know if these sharks are capable of learning from other individuals.

CS: What was the most challenging aspect of conducting the study?

CVP: One of the most challenging aspects of working with shark cognition is having enough space and time to test an adequate number of individuals. Port Jackson sharks are relatively small, do well in captivity, and are easy to handle, making this study possible. Another common challenge is maintaining the sharks motivated and avoid satiation. We weighted each individual at the start of the experiment and adjusted the rewards to their weight, to make sure they were not overfed.

CS: What were the best and worst aspects of data collection – any funny stories? Any specifics about working with sharks?

CVP: I was very fortunate to be based at the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, in Chowder Bay, a beautiful location by the water in Sydney Harbour. I spent long hours running trials but I could always jump for a swim or a snorkel at lunch breaks or at the end of the day. As anyone that has run long experiments will know, days are repetitive and exhausting, and Chowder Bay really kept my sanity and upbeat spirit. Releasing the sharks at the end of the experiment was also a major highlight. We got to be away from the office in gorgeous Jervis Bay, celebrate the end of the experiment with a swim, and see the sharks back in the wild. This location also made for some of the worst aspects of running experiments there. It’s not easy to access the aquarium without a car, and the building is old and not weather-proof. Sydney gets heavy rains from time to time, and one week it turned into a storm; a tree fell and blocked the road to the aquarium. I was in the middle of trials and didn’t want to interrupt them. And so I hiked half an hour through a steep path going down to the bay, under the rain and through fallen branches, spent all day freezing cold, with wind and rain slipping in through window and door slits. The worst was of course to hike up through heavy rain again; the path became a small stream and I was drenched in minutes. But in the end, I don’t regret it and would probably do it again!

Publishing

CS: How did you manage the writing process? Was it straight forward, or were there challenges?

CVP: This may be an unpopular opinion, but I enjoy the writing part too. This was also one of my last PhD publications, so I was on a roll and it all came together quite smoothly. I tend to save papers that I consider well written and that I enjoyed reading to later use as inspiration and guideline on structure and phrasing. My collaborators and supervisor were also very fast in revising the manuscript and had very good feedback, so I really can’t say this was a tough one to write.

CS: How was the peer review process?

CVP: The paper is published in Animal Behaviour, but we first submitted elsewhere and got a desk rejection. This wasn’t too unexpected, some journals give a big emphasis on novelty and our results were not entirely new; there had been a study showing that lemon sharks can learn socially, and the concept of social learning in solitary animals is also not new, even if not tested in sharks. The feedback was fast, so it didn’t drag the process too much. We decided on Animal Behaviour next and received very positive comments. The submission and review process was relatively fast and I like that they’re not too strict with the format. We had to do some minor revisions and the paper was out not too long after. Animal Behaviour is a reputed journal and has the audience for our work, so I am happy with how it turned out.

What’s next?

CS: Will you be following up on this research? What questions interest you next, based on your findings?

CVP: One of the ideas to follow up this work was to continue the experiment and test if we could establish a transmission chain of the learnt behaviour, which would be an indication of cultural transmission. This hasn’t been tested in elasmobranchs and is an important part of the idea that migration routes are socially transmitted in Port Jackson sharks, and perhaps other species. Unfortunately, we needed a large number of naïve sharks to do this and it wasn’t possible within the time I was in the lab.

CS: As early career researchers, we’re always learning. Is there anything you’d do differently in future, based on your experiences conducting this study?

CVP: I would perhaps change the task design to resemble a more naturalistic foraging route scenario; these sharks are bottom-dwelling and the juveniles eat mostly polychaetes hidden in the sand. We could use different arrangements of rocks to mark the food sources. That brings additional logistical issues in running trials but makes the task more ecologically relevant. On the other hand, if a naturalistic setting facilitates learning too much, we loose power to detect differences in the groups; so perhaps our task design was indeed a good choice for what we wanted to test for.

CS: Finally – what do you think are some of the big questions / challenges facing the field of cultural evolution and social learning?

CVP: I think one of the challenges of taking a broad look at the evolution of social learning and culture is that many vertebrate groups are still underrepresented compared to mammals and birds. Is the answer to how and why it has evolved generalisable across groups?

In the case of fish and sharks in particular, I would also like to see a merge between the fields of social behaviour and social learning with tracking and movement dynamics studies; I think the potential bias that can come from social learning and culture is an important addition to movement modelling.

CS: Thank you, Catarina, for granting us with some insight on your fascinating research with Cultured Scene!

The publication:

Dr. Catarina Vila Pouca is a postdoctoral fellow at Stockholm University, Sweden, and Wageningen University & Research, The Netherlands. She studied movements and behaviour of blue sharks off the North Atlantic and the cognitive abilities of the charismatic Port Jackson sharks from Australia. With time, her career has taken her to different waters. She is now more interested in understanding the evolution of behaviour and cognitive abilities, still focusing on sharks and bony fish if she can. She is currently working with a fascinating and classic system for behavioural ecology and evolution, the guppies of Trinidad. (Photo credit: David J Mitchell)

Catarina’s personal website: https://catarinavilapouca.wordpress.com/

Follow Catarina on Twitter: @catarina_vp